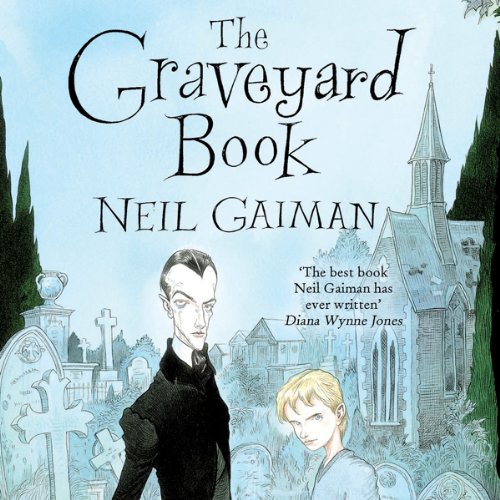

His voice as if dipped in rubbing alcohol becomes the other mother. The simple innocence of the tone is becoming on a child raised by ghost parents called Nobody Owens. A battered voice dipped in equal parts melancholy and arrogance makes the eldest of the Lilim turn into a wizened old lady from a childhood nightmare.

He is my companion — a giant shadow, a friend like Sirius on the horizon, and unobtrusive moon that is somewhere lost in the folds of the satin sky — for my midnight walks. His voice rings and trills and drums and pulses in one of my ears (one side of my headphones doesn’t work). The universe becomes multiverse as I find myself in a deluge of heard images and vibrating words that journey through the ossicles to set in my temporal lobe. They belong to me, from him to me.

I have been listening to the audiobooks of Neil Gaiman, read by Gaiman himself, as I take my nightly strolls. He takes me away, as my tired feet keep on with their rhythm, and rise above the tiled floor and walk into a fairyland. I am falling in love with his voice, even more so than his stories. Perhaps it is the witchy combination of the two that makes me feel a little less lonely, somewhat more alive when the air is filled with the faint whispers of desert coolers and the sleeping breaths of most people in my neighbourhood.

“I tend to think the experience of hearing a book is often much more intimate, much more personal: you’re down there in the words, unable to skip a dull-looking wodge of prose, unable to speed up or slow down (unless you have an iPod and like hearing people sound like chipmonks), less able to go back. It’s you and the story, the way the author meant it,” expressed Gaiman in his journal.

I love when people read to me, just like I rejoice when their hands go through my hair, ruffling me, pushing my body to deep awareness. Yes, it is intimate.

I remember asking the first person I was ever with to read a poem to me. In bed together, I was nestled in their arms. I opened the said poem (I cannot remember which, it was perhaps a Keatsian ode as I was a lot into Keats back then) on my cell phone. Their voice made an enclosure for us, closer and more comfortable than the four walls or the late afternoon light filtering through the dust-caked window screens. I recognise the memory of hearing, more than the touch itself.

Another time, another person who anchored at this violent shore for an evening, that is to say, it was a hookup. They sent a poem after a couple of days. A written verse, not spoken, about all that I left on their bed to their safekeeping. The scent, a stroke of my fingers, a pause that lasted. It was beautiful in its composition and still, I imbibed it in my mind as if they were reading it to me. The voice, more than the words, found its place in my skin.

What is it in the voice — the shape and sound and stillness of words and their absence thereof — that creates this web for me? Why do I reflect so much on the simple romance of people reading to me?

In a world where we derive pleasure from the visual medium (for instance in pornography where the voice, when present, is but a conduit to artificially heighten the stimuli) in the absence of a sexualised touch? What is voice but an afterthought, something dispensable, something that we can do without to reach the state of release or orgasm?

I am not denying the pleasure derived from listening to a pop song or an orchestral crescendo. I am trying to derive a loose hierarchy of senses to understand what comes first and what matters more that attracts us. I am not talking about phone sex either as it corresponds to particular acts being voiced and exchanged and therefore, the voice is in some ways subservient to the physicality of the actions.

Let me ask you to reflect on something. Think of the sexiest voice that you have heard, listen to it, feel how your body responds to it, and think of the person behind the voice and then yourself in tandem with that image. Is it similar to the response of Joaquin Phoenix’s character to the Scarlett Johansson’s AI-voice in Her?

“The voice is ambiguous, ambivalent, and enigmatic. We don’t

trust things we can’t seize with our eyes and hands. We might squeeze

the beloved’s body in passion or fury, but we can never hold his or her

voice hostage,” writes cultural theorist Dominic Pettman in his book Sonic Intimacy: Voice, Species, Technics (or, How To Listen to the World).

The voice, devoid of the body, is such a strange thing. When we say someone’s voice touched us or made us see an entirely new world, we are defining it by a more specific sense because the voice unto itself does not command the same expression. Still, we are defined by it, and it is characteristic — its tonality, rhythm, pitch, range, et al. — of our personality.

When I think of the voice behind those two poems, whether I heard them or not, I map out the entire person, how I saw their skin and all that lies beneath, how I perceived their lips and tongue and the throat producing those sounds that make a voice.

When I listen to Neil Gaiman, I think of his voice apart as well as a part of the story he weaves and constructs with its plot devices and endings.

In any case, I love it.

Read to me. It may be a bit more or less than romance. It is not always about desire and pleasure. Just read to me so that we can know each other better, as when I take from your voice, I give myself to you too.

…

This is the second essay in a new series of essays called #Trash. You can check out the previous piece here. As promised, I wrote something sexier as compared to last week. Let me know what you think about this essay, what voices left an impact on you, as well as some good audiobook recommendations. I welcome your feedback and topic suggestions as I would like to keep going with this series at least for some time.

If you liked this piece or anything I have ever written, please consider showing your support for my work by sharing it with others and making a small contribution. Thank you.